Some days it seems the only happiness to be found is in the elusive oblivion of sleep. On those days the price for staying awake is high, tears the only outlet for a toxic broth of fear and rage against disaster I’m too small to change. When I feel like my kayak has capsized in the rapids, I try to return to the ritual of lighting a candle to Brigit, a ritual that symbolizes and feeds my faith in the light — that Great Love that kindled my inner flame, that light that can overcome any darkness. Then I’m a little better able to see difficult feelings as potential tools for survival: fear warns of danger, anger powers action, tears are a vital expression of sorrow. To balance and bear these emotions I’ve learned some coping strategies from friends over the last few months that help me access the light and nurture my inner flame.

1. Keep things in perspective.

The sweep of history is long, holding meteor strikes and ice ages, the rise and fall of civilizations, cities destroyed and rebuilt. Positioning the current calamity on that long arc lets you view it in a different way — it may be overwhelming now, but it won’t always be. In my late thirties infertility and divorce seemed like the defining events of my story. Now at age 63 they are simply chapters in a much longer book. If this is the case with a lifetime, it is even more so for a country. In just 250 years the United States has witnessed a successful fight for independence from empire and civil war; Americans saw the excess of the Gilded Age give way to the corrections of the New Deal.

To be clear, the suggestion to keep things in perspective comes with a few caveats. For one thing it can feel limited to the privileged. Perspective might not be available to me if my home had been bombed or burned, if I had just lost my job or feared being deported. Nor should it provide false comfort that things aren’t really that bad. “Pay attention” was Mary Oliver’s first instruction for living a life, which means noticing goodness and beauty but also recognizing tragedy and treachery. Perspective doesn’t minimize calamity, it places this knot of suffering in a larger tapestry. Yes, what is happening now is unprecedented, but as a friend told me recently, we’ve been here before, and we know what to do.

2. Seek sustenance in nature.

My favorite tree when I was growing up was the pine in our backyard. In my essay “The Secret Forest” I describe it as “a bit of the wild in our tract house neighborhood where my sisters and I could climb, build a clubhouse, or imagine elves and fairies. The green needle canopy of that single pine, its sappy branches, duff carpet, and unique scent formed an entire arboreal world, Sherwood, Narnia, Fangorn Forest. And when I tired of company and play, it became a place to hide out, just the pine tree and me, my first hermitage.” Even as a child I understood the solace to be found in nature.

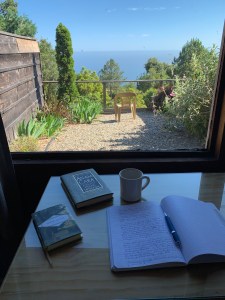

Now more than ever, go outdoors and open your senses wide. Try closing your eyes. What do you hear? Smell? Take off your shoes and find a place to plant your bare feet. As I write, I’m imagining the sensation on my soles of hard-packed sand, cushiony grass, moist and loamy garden soil. Walk among the trees. Press your forehead to the trunk of the redwood and lay yourself down in her duff. If you don’t have a place nearby to forest bathe, look up. On busy days, I like to take what I call “sky breaks” to savor for a moment whatever that immensity above me has to show.

3. Lean into community.

Even an introvert like me needs community. Now is the time to seek deeper connection with yours. Another caveat: social media might not be the best way. Instead gather with friends, go to church, play pickleball. I see people around me engaging in all kinds of ways: singing in a choir, taking a dance class, volunteering, joining a protest. Does all that sound ridiculously beyond what you have the capacity for right now? Text a friend and ask her to light a candle for you. (Or email me, my candle is ready.) Next week you might have the energy to meet for coffee.

4. Find joy in the ordinary.

For several months last year, caring for my aging parents meant spending more time than I ever had before in the emergency room and ICU. My sisters and I were inundated dealing with doctors, insurance companies, and attorneys, trying to arrange at-home care and then assisted living, reacting to one crisis after another. In the midst of this, my mother shared advice that her spiritual director had given her when Mom was caring for my grandmother. You might expect a nun to encourage you to honor your parents or pray the rosary, but that was not this sister’s approach. Instead, she advised my mom each and every day to look for joy.

When I tried it, I had the same experience Ross Gay did when he started writing an essay everyday about something delightful. He discovered “that the discipline or practice of writing these essays occasioned a kind of delight radar. Or maybe it was more like the development of a delight muscle. … Which is to say, I felt my life to be more full of delight. Not without sorrow or fear or pain or loss. But more full of delight.” Now the same thing happened to me: I developed a joy radar. A perfect feather from a hawk on the wing floated down into a crosswalk just as I was about to step off the curb. A friend’s baby granddaughter flashed me a bubbly smile. Soon my sisters and I were texting each other our daily joy, multiplying the effect.

***

As I struggle for equanimity, I find encouragement in a letter written almost two thousand years ago: “Let us lay aside the deeds of darkness and put on the armor of light.” This was St. Paul to the early Christians in Rome, and by light he meant love. Why then does he choose such a martial metaphor? I personally would rather draw a cloak of kindness around me than put on a suit of armor. But choosing love in challenging times takes great courage and fortitude, and I want to feel protected when I go out into the world, not by weapons, not by metal, but by light — the great love that kindled my inner flame.

Nature, community, joy — it may sound corny, but these are rays of light, and you can probably see how they feed each other. Moments of joy are highly likely when you’re stargazing or line dancing at the community center. In the life of a redwood this moment is a blip, and connecting with the world beyond your immediate crisis can shift your perspective.

Darkness does not have the last say. No matter what happens you are held in the great web of life.