Strolling through the center of Kildare, you can’t help stepping into Brigid’s footsteps: this figure revered as Celtic mother goddess and Christian saint smiles at you larger than life from murals on McHugh’s Pharmacy and the Firecastle Pub. Since 2012 I have been part of a circle in Santa Cruz acting to keep Brigid’s legacy alive, so it was with the spirit of a pilgrim that I spent an afternoon around the corner from the pub at the site of the fire temple where a flame was kept burning in ancient times to honor the goddess and later the saint who bore her name. For centuries before and after Christianity came to Ireland, women tended that flame to the sacred feminine until it was extinguished during the Reformation.

Leaning against a stone wall that marks the old boundary of St. Brigid’s monastery, I pulled out my iPad for some writing en plein air in a field of green grass dotted with white alyssum, yellow cat’s ear, and old gravestones. Gray clouds drifted across the sky, and birdsong mixed with the distant hum of traffic from town, clattering from the restoration of the medieval round tower on my right, and soft-voiced visitors drifting into the cathedral. Before me was the fire temple, surrounded by a short rectangular wall with stairs leading down to a depression in the earth, empty now as a breeze danced through the sea of yellow flowers. Once upon a time this enclosure might have been round instead of rectangular, formed by hedgerows instead of stone. Long ago it did not share this field with a Christian church and cemetery; now it does, a tangible reminder of how devotion to the goddess transformed into a fidelity acceptable to those in power, transformed, but in the red-hot heart of the fire, one and the same.

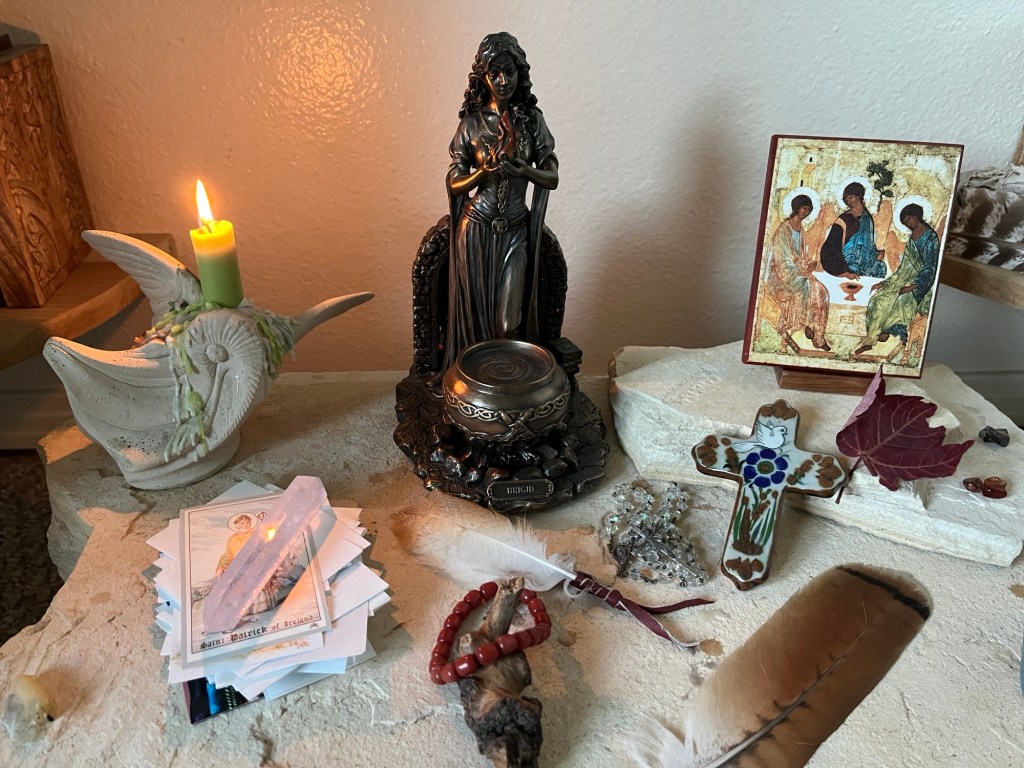

This is part of why Brigid appeals to me: she accommodates a Christian sensibility, and she holds the ancient impulse to honor the sacred feminine, just as that primal instinct lives inside me along with the Catholic tradition I was born into. In the heart of the fire and in my own human heart they are one and the same because each mirrors the spark of the One beyond all names and forms and even gender, the fire inside each of us meant to be the light of the world.

In 1992, as a new millennium approached, the Brigidine Sisters in Ireland began a process of discerning their mission which led to opening a small center for Christian Celtic spirituality in Kildare called Solas Bhride. A year later they re-lit Brigid’s flame in the market square of Kildare, carrying a spark of that flame to Solas Bhride where they have kept it continually burning ever since. Our retreat group spent a morning and an afternoon with the sisters there, learning about what Brigid can teach us today about caring for the planet, hospitality, peacemaking, and contemplation. The main building is constructed of circular rooms in the shape of a Brigid’s cross, and in a concluding ritual in the round room where a pillar candle burns with Brigid’s flame, we each lit a tea candle from that original ceremonial spark of 1993. As part of the Santa Cruz Brigid’s Circle, I take turns with eighteen other women tending her flame, and it thrilled me to carry the seeded wick of that little tea candle back to Santa Cruz to light my candle at home.

During those days in Kildare, it occurred to me for the first time that the real flame I’m tending is the one inside me – kindled by something greater than me but my responsibility to keep burning. How to do that? Fire needs oxygen and fuel. For each of us the fuel may be different. My flame feeds on contemplation and connection to community, nature, and the Divine. (Therapy, books and chocolate help too.) Fire can also be smothered or doused. I confess, this year anxiety has dimmed my inner flame, the big problems of the world that don’t diminish the little ones in my personal life even though I try to keep them in perspective. At two in the morning the challenges of my aging parents keep me awake as much as climate change and the political divisions cleaving our country. But when I’m anxious or afraid, my inner light can’t shine outwards the way it’s meant to. Maybe mindfulness practices like meditation and deep breathing, practices that calm anxiety and help put fears in perspective, are vital tools in the basket of a flame tender.

Years ago, when I was in thrall to some trouble I’ve forgotten now, a friend placed her hand on my chest and told me, “You can come from a place of fear or of love.” How many times did Jesus tell his disciples, be not afraid? This might have been more than a beloved teacher’s reassurance to his frightened friends and followers. Maybe it’s the prerequisite to the greatest commandment of all, a key for each of us to tending our flame.

As I write, we have just passed the midpoint between the autumn equinox and winter solstice with celebrations of Halloween, All Saints Day, Dia de los Muertos, Samhain. The days are getting shorter and cooler, and we may feel trepidation at the darkness ahead. How to tend my flame now? In a time of trouble when I am susceptible to fear, it begins with faith in the light. The feast day of St. Brigid is celebrated on February 1st, the cross-quarter day between the winter solstice and spring equinox known as Imbolc in the Celtic calendar when the goddess Brigid is also honored. At the beginning of February winter isn’t over yet, but we feel it yielding. Lambs are born, crocuses bloom, and sunrise comes earlier; light lingers a little longer each day. In this way Brigid reminds us (in the words of a song by Cyprian Consiglio): “There is a light that can overcome the darkness. There is no darkness that can overcome the light.” Even now our flames can be vibrant — especially when joined. The ritual of lighting a candle to Brigid both symbolizes and feeds my faith in that light. Fear is a bushel over the lamp. Love is the array of lighthouse mirrors that reflect it far out to sea.