In a collision of the secular and spiritual, Valentine’s Day happened to fall on Ash Wednesday this year, two days I treasure in seeming conflict. While a bouquet of red roses and pussy willows graced our dining table, a cross of ashes was traced on my forehead; in deference to the call to fast the heart-shaped box of chocolates remained unopened.

Lent calls Christians to pray, give alms, and fast. I’m good with the first two but struggle with fasting. Life brings enough loss and deprivation. Why add to it? Each year I wonder how I will answer the ubiquitous question, What are you giving up for Lent? In childhood it was usually candy or ice cream; as an adult I graduated to alcohol and chocolate and recently started using the season as a way to try new habits like using less plastic and being vegan before six. Whatever personal practice one chooses for Lent, on Ash Wednesday and Good Friday Catholics are supposed to eat less, specifically only one full meal and two smaller meals. Compared to Jews who eat and drink nothing at all on Yom Kippur or Muslims who refrain from food and drink from dawn to dusk for the entire month of Ramadan, this Catholic fast is not a big ask, but for a privileged American grazer like me it’s surprisingly hard. My relationship with fasting is complicated by my teenage experience of anorexia, two years of starving myself into a 93-pound scarecrow followed by a long recovery. I was saved by my caring family, a helpful therapist, and the slow gift of grace, but almost fifty years later the sensation of hunger takes me back to that fraught and troubled time. I tell myself that in those days I fasted enough for a lifetime of Lents.

And yet this venerable tradition attracts me. A religious act practiced in so many different faith traditions must have something going for it. What drew Jesus at the age of thirty to retreat to the desert and fast for forty days and forty nights? All scripture tells us is that he was led by the Spirit. I like to think of his time there as a kind of vision quest. His cousin John had just baptized the young carpenter in the River Jordan, and he would return from the desert to begin a public ministry, preaching and healing all over Galilee and Judea, burning with the good news that the Kingdom of God was at hand.

Last month I tried Dry January for the first time. Although I usually only have one glass of wine or one cocktail with dinner, I drank pretty much every night, and I was curious what my body would feel like with no alcohol in my system for an extended period of time. The answer was “pretty good,” but nevertheless as dinner time approached each evening, I felt anxious and deprived; after the meal I was glad I’d abstained except for knowing I’d have to go through the same sacrifice again the next day. January felt like the longest month ever!

So what kept me going? First (and most crucial to start out with), accountability! I’d mentioned to my mom and sister that I was doing Dry January, and even if they didn’t care one way or another, I didn’t want to admit to them that I failed. Second, community. Dry January is a thing. My sister was also abstaining and cheered me on; my sweetheart committed to “Damp January,” so most nights he wasn’t drinking either. Articles and podcasts offered support, and when I was with friends, Dry January was the only explanation necessary for declining a drink. Third, I approached the experience with a spirit of curiosity. How would it feel? What would I learn about myself? What surprised me most were all my reasons for drinking. It was a reward for working hard, consolation for the blues, relief from anxiety, a celebration of romance. In fact, I only cheated one time — when I arrived home from a four-day retreat to find Ben Webster love songs playing on the stereo and Tom cooking my favorite dinner. How could I resist indulging in a glass of wine with him?

The thing is alcohol was only a temporary balm for depression or anxiety, and likewise my sense of deprivation each evening was also temporary. I liked the new feeling of clarity and energy after dinner. Although I obviously wasn’t getting drunk on one drink a night, even slight inebriation is different from sobriety, and ultimately the freshness of 100% sobriety is probably what helped me stick with my commitment. Now that the longest month ever has come to an end, I am drinking again, but it’s no longer the default.

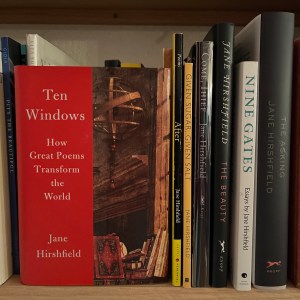

So what am I giving up for Lent this year? Inspired by Christine Valters Paintner, the online abbess at Abbey of the Arts, I’m trying A Different Kind of Fast. In this beautiful book, she suggests a different practice for each week of Lent, a pattern or way of thinking to give up and a corresponding new pattern to embrace, for example, fast from multitasking and inattention and embrace full presence to the moment. The intention is to feed our true hungers, which are obviously not for chocolate or alcohol (as much as I’m enjoying a mocha as I write this!) but for something deeper and lasting.

Each of us has unique desires, but I suspect we all share a common yearning for connection and a sense of purpose. In short, as trite as it might sound, we hunger for love. I imagine that for Jesus, fasting in the desert was a radical act of purification that not only opened the ears of his heart to the voice of the Divine but actually fired him with the energy of Divine Love. Maybe starting Lent on Valentine’s Day was not such a crazy collision after all.